“Did you see that?!” Corkle yelled. Jonathan McCorkle, or “Corkle,” as he’s known, was shouting into my ear during a show at Snug Harbor. It was the same Scowl Brow show where Jerry crowd surfed. “This is my favorite local band,” he said, “because every time they play it’s a beer shower.” He was soaked.

I met Jonathan when he worked at our store, and he’s been one of my main links to the fixie scene. Jonathan is a member of W.A.R., and he has introduced me to the leaders of his club, Lauren and Greg, as well as several other fixie kids. I’ve seen Jonathan partying in his natural habitat on a number of occasions: jovial and intoxicated at Common Market, the Banktown Brawl bike event and Jerry’s alley cat race, which he won, speech-slurring drunk.

Yesterday I joined him and a couple dozen others for an alley cat at Veteran’s park, hoping to find a story. I arrived just in time to watch a dozen riders gather in the parking lot and set off on a ten-mile race. I sat out; I didn’t have a brakeless fixed-gear bike, the only kind admitted.

Half of the racers were my coworkers. After 20 minutes, John “Mailbox” and Trey came flying down the hill to tie for first at the pavilion finish line. Trey showed off a flat tire he’d ridden on for miles. Jonathan was third. “I’m really drunk,” was his excuse. “I drank a lot before this. Like four beers and two Red Bulls.”

Later, I somehow managed to win a 24-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon in a track stand competition. (Track standing is just balancing, stopped, on a bicycle.) “What am I going to do with this?” I wondered. I was sure my victory was solely due to my being the only rider even close to sober.

I shared my winnings. “Can I grab like two of those?” Jonathan said, reaching into the box. Almost a dozen cans were gone before I left. For hours the crowd of young men caroused, rehashing dramatic moments of the race, shouting over each other, drinking and smoking. Of the 30-person turnout, only five were women.

I was struck by the ease with which everyone got along: skate kids, girlfriends, someone’s mother, black kids and white kids, interacting seamlessly and enthusiastically. They shared a bond deeper than any demographic. They shared alcohol.

Earlier this week, on Monday night, I visited Jonathan’s apartment to record an interview. It was after ten, and we stood outside behind his apartment. “I can’t afford cable so I don’t watch cable,” he told me, pausing to draw on his cigarette. “And there’s a lot more of like a social scene up here. So it kind of makes you lose a little bit of touch with the outside world.”

We were talking about Plaza Midwood, the neighborhood we stood in. I had been picking Jonathan’s brain about Common Market and Charlotte bike culture. We went inside and sat down in his room, surrounded by bike parts hanging on the walls.

I asked about Jonathan’s life philosophy, mentioning Jerry’s and my discussion on the same topic. “What did he say? ‘You drink a lot and party hard and then you die’?” he asked, laughing. “I do a lot of that,” he admitted. No kidding. But what he told me next surprised me.

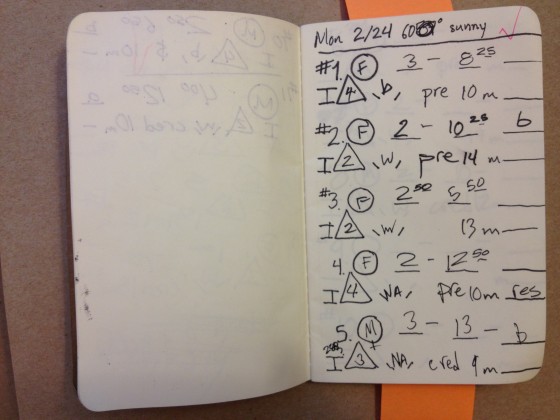

Jonathan said he’s been on break from a 2-year program in Geospacial Technologies at CPCC. He talked about his interest in map-making, producing a text full of Greek letters and trigonometry. “Man, it’s been a year and a half since I’ve seen any of this stuff,” he said. “I’m starting to forget. Doesn’t help that I smoke weed.”

He said he only had 3 or 4 credits left to complete his program and transfer to Appalachian State. He admitted that getting a degree was mostly a tool to make more money. “I just had to quit going to school so I could work full-time to afford living up here. I wasn’t trying to live with my parents forever. I didn’t have any extra money left over so I just haven’t been back to school.”

I was impressed. Just think, Corkle, the consummate party kid bike punk, a number-crunching, career-oriented academic. Jonathan paused to reflect for a moment. “But I’ve had fun since then!” he added.

Recent Comments